In the following account, participants in the noise demonstrations targeting hotels that house federal agents in the Twin Cities recount their experiences and explain how this tactic might be employed elsewhere.

January 26, 2026.

On Monday, January 26, a hundred protesters converged on the SpringHill Suites by Marriott in Maple Grove, Minnesota to see off disgraced former “Commander at Large” of Customs and Border Protection Greg Bovino, freshly demoted and set to be shipped back to California. Demonstrators blew whistles, beat snare drums, and banged on pots and pans. Border Patrol officers collaborating with local police responded by shooting tear gas and pepper balls and shoving people indiscriminately, arresting at least two protesters.

This was the latest in a series of noise demonstrations targeting the hotels housing this occupying force. So far, multiple hotels have closed as a result, and it is conceivable that some mercenaries have gone without rest, as well.

Two days after the Whittier neighborhood chased out federal agents following the brutal murder of Alex Pretti, the regime chose to rotate out Bovino as the public face of the federal occupation. His “Commander-at-Large” position has been abolished. This will reduce the number of federal mercenaries occupying the Twin Cities by at least one, but it leaves thousands of Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents to continue terrorizing us, now likely with more assistance from the Democratic governor and mayor.

January 26, 2026.

Nonetheless, this is the first crack to appear in our oppressors’ armor. They are not making this concession because they murdered Alex Pretti, but because the people fought back. The struggle is far from over—Immigration czar Tom Homan will be arriving to replace Bovino soon, and we will have to pivot to confront a new strategy. But it is instructive that CBP BorTac officers, who were the most theatrically violent agents in the first act of this invasion, are the first to withdraw from the fight after suffering a single defeat, the way cowards do.

What happens in the Twin Cities is a prelude to a much larger struggle that will unfold around the country. We can help to equip you to fight these same bounty hunters when they show up in your town by sharing the tactics with which we are fighting them here. Alongside the rapid response networks, the general strike, the blockades, and the revolts when they shoot people, we have been experimenting with noise demonstrations.

Here is what we have experienced, so far.

January 26, 2026.

The Noise Demos

The first noise demo I attended was at the Home2 Suites by Hilton in Bloomington, Minnesota by the Mall of America. This was very early into the occupation, when rapid response was still being run primarily out of South Side networks and had yet to proliferate through the rest of Minneapolis and the greater metro area. I saw an infographic shared in the daily patrol chat, asking for people to attend with noisemakers and not to post about it on social media.

When we arrived at the hotel, there were about a dozen protesters and four Bloomington Police squad cars waiting in the parking lot with their lights on. The word on the ground was that the Signal loop being used to plan the demo was infiltrated, necessitating the creation of a new, somewhat vetted planning chat on the spot. We did a lap around the hotel banging pots and pans, blowing whistles, playing brass instruments, and setting off car alarms. When we finished our lap, we pressed on and did another. Then the squad cars drove up to block our path and we left.

The group that emerged out of this demonstration involved all sorts of everyday people, but it was de facto headed by representatives of a certain longstanding formal organization, which published recordings of the demonstrations and claimed responsibility for them. To give credit where it is due, the experience, confidence, perceived legitimacy, and organizational capacity of this larger public-facing organization may well have been essential to popularizing noise demonstrations as a tactic in the Twin Cities.

January 25, 2026. You can obtain these stickers here.

The strategy has involved two kinds of demonstrations:

- Smaller, invite-only noise demonstrations that are promoted only to those the planners trust—these generally draw 10 to 25 attendees, which is still enough to wake up an entire hotel, and

- less frequent publicly-announced noise demonstrations involving self-appointed protest managers in yellow vests, ready to direct the much larger crowd.

Regarding the invite-only noise demonstrations, the group quickly coordinated new ways to identify and protest at hotels that were collaborating with the fascist occupiers. Some people would go to the hotels, acting like guests, and ask workers if they had heard anything about ICE staying there. Others would follow up on tips by scouring hotel parking lots for confirmed ICE license plates. When one worker was fired for tipping the planners off that ICE was staying at their hotel, people developed online forms for anonymous tips.

Everybody brainstormed new ways to make more and more noise. Full drum kits quickly became a mainstay of the demonstrations, showing up in both stationary and mobile forms. One person brought handheld personal alarms that poduce a high-decibel noise when a pin is pulled and do not shut off until the pin is replaced. These devices, widely distributed among the participants, made for quite a headache for hotels when left behind in inaccessible locations after protesters departed with the pins. People began to bring powerful flashlights, shining them into the windows of hotel rooms.

To decide on a time and location, the participants would create a new chat for each demonstration, picking a nearby location at which to meet and discuss the specifics of that night’s plan. One innovation has been to start by setting off car alarms for an agreed-upon amount of time, then leaving our vehicles to make noise on foot, going around the hotel in laps. When the police show up and issue a warning, we leave, reasoning that smaller groups are not as effective at resisting those orders as a massive crowd is.

Eventually, people began to prepare a list of hotels to target on a given night. We’d protest at one hotel until the police arrived, then simply move on to the next in another neighborhood or even city.

January 25, 2026.

In late December, comrades had gotten word that there were feds staying in the Canopy by Hilton in the Mill District of Minneapolis and, once again, the Home2 Suites in Bloomington by the Mall of America—the same location mentioned above. The plan that night was to meet up at midnight nearby to go over how we wanted to start the demonstration. Certain people took on specific roles: one person would be police liaison, another would de-escalate angry bystanders and try to recruit them into the demonstration. Our goal was to ensure the demonstration could go on as long as possible, even after local police departments showed up to shut it down.

The action at the Canopy started shortly after midnight. It drew a larger crowd for one of the smaller demos. Folks had brought a wide range of noisemakers with them: pots and pans, speakers, whistles, an entire drum kit, megaphones, even a didgeridoo. A few also brought flashlights and a laser pointer to shine into the windows of hotel rooms. Staff inside of the hotel quickly called the cops to quash the commotion, but the police responded slowly.

The noise was audible from several blocks away in multiple directions. Neighbors from many apartment buildings came outside to check out what was happening. Someone even hopped out of their car to hand a demonstrator an airhorn, then circled the block honking their car horn! Roughly 20 to 30 minutes into the demo, a few Minneapolis Police Department squad cars started to show up, driving slowly by the demonstration, but the officers did not exit their cars or declare the crowd to be trespassing.

At one point, there were four squad cars stationed at the end of the street to the left of the demonstration, presumably chatting about how to engage with the protesters. After what appeared to be a lengthy discussion, they departed.

The noise demonstration went on, uninhibited by police or angry residents, for a solid hour. My companion and I left the Canopy location to head to the next meeting spot in Bloomington. After we had left, comrades who were still at the Canopy by Hilton lingered to speak to press about the action. Shortly after that, MPD rolled in with an absurdly heavy-handed show of force. According to our comrades who were still present, they showed up with a dozen or more squad vehicles—one activist joked that there was one car per police officer that responded to the demonstration. An officer on a loudspeaker announced that the activists had to leave and declared the action an “unlawful assembly.” No arrests took place.

After the action at the Canopy, our comrades rendezvoused with us in Bloomington to establish our plan of action for the next hotel. It was cold and raining, so we decided to keep it short and sweet. We drove into the hotel parking lot and set off our car alarms for a few minutes before getting out to do a couple laps around the hotel making noise. The police responded differently to this demonstration than they had to the one earlier this winter. They weren’t already stationed there waiting for us, but their response was quick. The officers who responded told activists to leave the premises immediately or be trespassed.

January 25, 2026.

The first of the public demos with mass attendance took place in Edina, an affluent suburb of Minneapolis. The crowd easily numbered around 200. More and more people showed up throughout the night, a common feature of noise demonstrations. The crowd was furious, but the atmosphere had the energy of a party. Protesters danced and laughed and socialized when not using their noisemakers. Some identified the vehicles of the federal mercenaries and exchanged notes about how to recognize them. The organizers tried to keep the crowd on the sidewalk and off of hotel property, in hopes of delaying a police response, but largely failed in this effort.

For the first time, ICE agents staying in the hotel walked into the lobby in plainclothes with their faces masked in order to watch the uproar. This incensed the crowd, many of whom charged up to the doors and windows to scream at the occupiers, pound on the glass, and shine strobe lights in their eyes. When one fed attempted to blow off the crowd by visibly watching basketball highlights on his phone, a protester shouted “You’re watching ads, you broke bitch! Kill yourself!” The federal agent returned to his room shortly thereafter.

January 25, 2026.

Each time the crowd began to directly confront the federal agents, yellow-vested peace police desperately sought to corral the demonstrators into taking another lap around the hotel. Again, these efforts met with only moderate success. Eventually, two Edina police officers arrived, placing themselves at the hotel’s front entrance. They tried to give a dispersal warning but were completely drowned out by of the protesters.

You should wear earplugs at any noise demo—my tinnitus has taught me that lesson well.

The protests marshals decided their job was to do the work of the police for them. They told everyone it was time to disperse. A large segment of the crowd didn’t listen, and the marshals simply left. Police repeatedly attempted to disperse the crowd by issuing warnings, without effect.

Finally, Edina police and officers from four neighboring police departments all showed up in riot gear, declaring an unlawful assembly at the whole hotel and the surrounding blocks, and threatened to deploy chemical weapons. When the thinning crowd of protesters saw that the police outnumbered them, they left, having averted arrest or injury. At this point, there were five different police departments standing around protecting the property of the collaborators.

In this case, the protesters escalated to the maximum possible extent, then decided for themselves when the situation was no longer favorable—a decision that the protest marshals had tried to reserve for themselves.

January 25, 2026.

January 25-26

These protests were effective at their intended goals. Multiple hotels eventually ceased to house the murderers, even after the demonstrations had ended, and some hotels in St. Paul shut down operations entirely.

Bearing this in mind, the initial organizers began to encourage other groups to plan their own noise demonstrations. The advantages of this more decentralized approach are illustrated by the demonstration that took place on University Avenue on January 25, one day after the summary execution of Alex Pretti and the ensuing street battles.

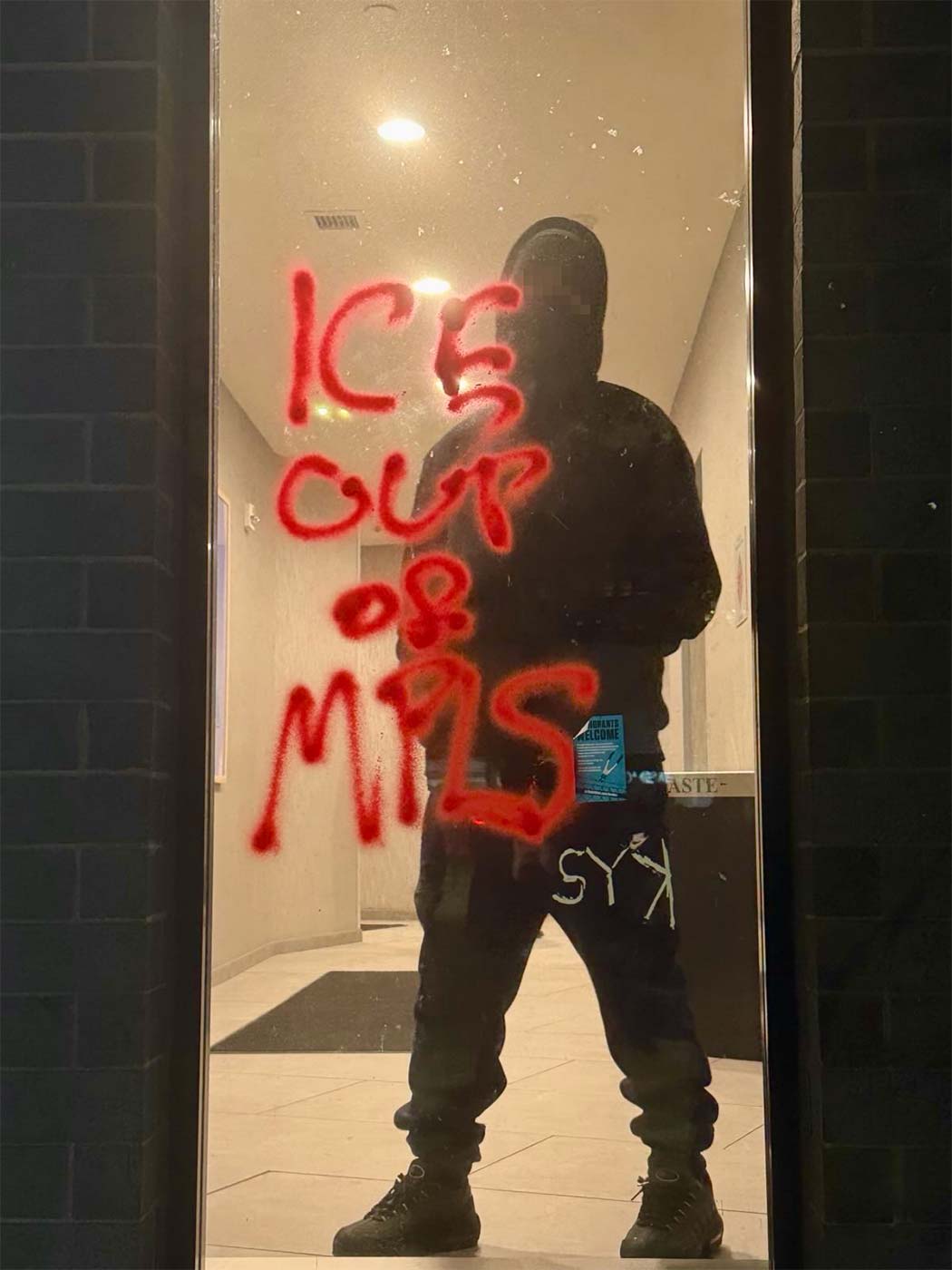

The participants in the January 25 noise demonstration had taken notes on what had worked in the streets. The clashes that established Alex Pretti square on January 24 were characterized by the rapid proliferation of barricades. On the night of January 25, by the time I could see what was happening at the Home2 Suites on University Avenue, trash cans, wood pallets, and mattresses had been pulled into the street, blocking off University Avenue on both sides of the hotel. The protesters made plenty of noise. At least one window was smashed, while the rest were decorated with messages including “Fuck ICE, ICE Out!” and “Killers stay here.”

January 25, 2026.

Some protesters pulled signs off the building; some entered the lobby and rearranged the furniture.

After at least two hours of this, for the first time, the feds took it upon themselves to respond to a noise demonstration directly, setting the stage for the demonstrators to break new ground. With the roads blocked off, the federal agents had to run in on foot from the side, filling the street with tear gas and shooting riot munitions into the crowd in order to enter the hotel.

Nonetheless, the demonstrators remained for a while, even throwing a metal pot at the head of a federal agent who was menacing the crowd with a riot shotgun in the front door. Eventually, scores of feds and Minneapolis police arrived in riot gear to clear the barricades and evacuate the ICE agents staying in the hotel. They arrested 14 people in the ensuing melee. The pigs held skirmish lines while a now smaller group of protesters to west of the hotel waited patiently on the sidewalk, heckling the feds. After roughly an hour, the feds drove off, once again filling the neighborhood with tear gas as they retreated.

After the police and feds left, the protesters went right back to the front of the hotel and began making noise and adding new paint to it for another hour. Minneapolis police returned in riot gear, this time with public works crews in tow, using the same bulldozers and garbage trucks they weaponize against unhoused neighbors to clear the barricade materials off the road.

Once more, protesters simply waited for them to leave, then resumed making noise. By the time I was no longer able to follow the events, the demonstration had gone on for six hours—the longest I’ve heard of by far.

January 25, 2026.

Takeaways

Public pressure campaigns can get the ball rolling. Escalation serves to achieve more immediate results.

- The less disruptive noise demonstrations helped to get people involved, but did not always accomplish their goals. Consistency is not enough; it is more important that the hotels and the authorities experience the movement as unpredictable. When self-described “peaceful” noise demonstrations took place at the same location a month apart, this simply resulted in a stricter police response the second time around. By contrast, the demonstration on University Avenue compelled the agents to evacuate before it was even over. The police protect private property, and corporations use that property to turn a profit on aiding the killers and kidnappers of our neighbors. Redecorating or otherwise transforming that property is a natural extension of the noise demonstration as a broader tactic.

January 25, 2026.

Pick your battles. Fight your enemy while they are at rest.

- The benefit of noise demonstrations is that they allow the people to confront their occupiers directly, on their own terms. This is different from patrolling, rapid response, and the street battles that break out each time a fed murders or kidnaps a beloved neighbor. By taking the initiative, the protesters are able to determine the conditions of engagement and gain the opportunity to press their advantage. For example, by temporarily leaving when overwhelming state forces arrived only to resume as soon as they left, the demonstrators on University Avenue were able to maximize the duration of their action, minimize the risk to their health and freedom, and compel the fascists to expend the maximum amount of resources. We should learn from this and incorporate this strategy into future actions. If the police do not know if we will come back, then every time we appear at a location, they will have to keep forces stationed there, stretching their troops thin.

January 25, 2026.

A good noise demonstration in progress advertises for itself.

- People broadly hate ICE. Revealing the location of the fascists and their collaborators politicizes and radicalizes those who witness these demonstrations. At nearly every one of these demonstrations, cars driving by honk in support. Many take several more laps in order to continue honking. These events are fun—they have an undeniably positive energy. Hotel guests even come outside to join us. Noise demonstrations help to demystify the occupation to neighbors, revealing the proximity and vulnerability of the occupies and the power that everyone has to do something about it.

January 25, 2026.

Appendix: Another Account from the January 25 Noise Demonstration

By early morning on Sunday, January 25, the autonomous zone that people had established around the site of the federal execution of Alex Pretti had dissipated. While the flowers and memorials around the vigil remained, continuing to draw mourners, the National Guard had removed the barricades around Nicollette Ave in the early hours of the morning. Those who were willing to put their rage to a purpose needed a concrete point of intervention.

The Party for Socialism and Liberation had called a march, but the march offered no opportunity to engage federal agents or ICE infrastructure. Fortunately, as described above, demonstrations directly confronting ICE where they slept were already happening consistently in the Twin Cities. Thanks to weeks of collective effort, several hotels had already been identified as housing ICE. A flyer circulated on Sunday only a few hours before the noise demo. Under other circumstances, this could have been too late to draw any participants—but thanks to the urgency of the moment, people wanted to come, and the last-minute announcement left the cops little time to prepare. When we walked up to the noise demo, there was no law enforcement around, federal or local.

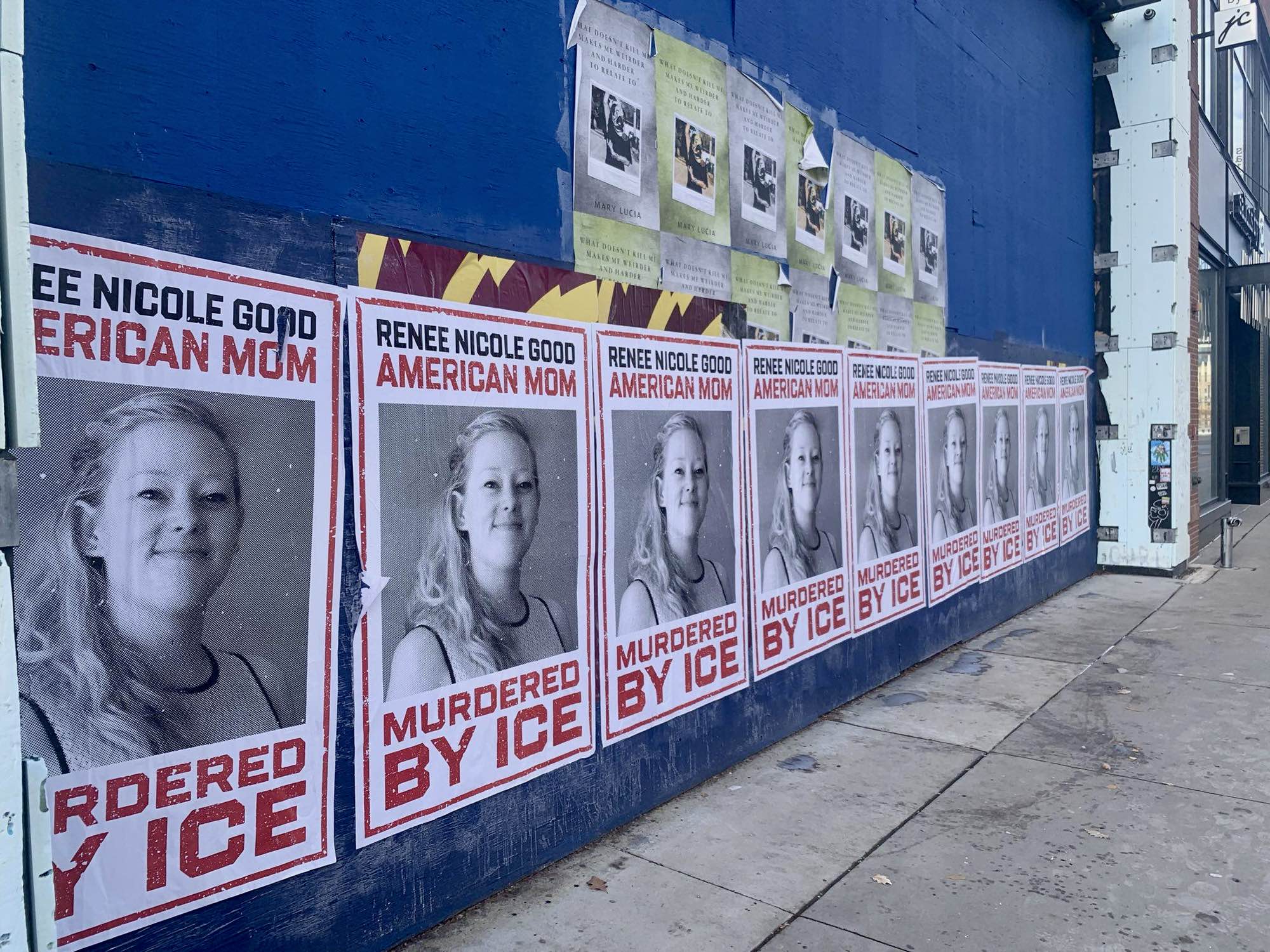

About fifteen people were already there, crowded around the glass walls of the hotel lobby, through which we could see several men who looked like ICE agents as well as some other hotel guests. The energy was high—someone had brought a small drum kit and another person had a percussion set and cymbals. People blew whistles, shook noise-makers, and blasted music on portable speakers. For an hour, we channeled our rage about the murders of Renee Good and Alex Pretti and the months of terror that immigrants had experienced in the Twin Cities into creating a loud, joyful, communal space. As the crowd grew, we spread out across the sidewalk, moving in front of the doors, where someone had spray-painted, “ICE OUT, ICE KILLS.”

People started moving into the street—first standing in the bike lane, then dragging a trash can into the road. Soon, people were grabbing any bin they could find, pulling pallets and old mattresses out of the alleys until they had completely blocked one side of the street. The barricade on the other side was smaller—a couple trash cans, a few traffic cones, and some parking markers from the hotel—but it sufficed to stop traffic. At one point, a man we suspected to be a plain clothes agent, who had been walking around taking notes on his phone, attempted to dismantle the barricade. People rebuilt it and he retreated inside the hotel.

City busses on each side of the street had to turn around or pull over. Multiple cars pulled up and parked, forming their own barricade. Families with children in their cars watched the demo from a safe distance: they cheered, honked their horns, blasted music, and set off their car alarms. In addition to noisemakers, people shined flashlights at the windows and set off a few roman candles. Agents could be seen looking out from their hotel windows with cameras or phones. On the street, there was a cacophony of trumpets and drums. People started kicking the trashcans to a beat, and we danced with friends and strangers.

The hotel had locked the front sliding doors and left a paper sign instructing guests to go around the back. We learned that ICE was going in and out the back, and people spotted men who had been seen filming us through the glass walls go out the back and leave in their cars. Maybe if the crowd had been bigger, there could have been more people watching the back of the hotel, in order to note which cars they used—an idea for future demos. Some of the people inside the hotel who were not agents seemed supportive. Others played ostrich—after someone delivered food from Sweetgreen and left it outside the locked front doors, a guy staying at the hotel went downstairs and pried the doors open to grab his delivery. By that point, the doors were broken.

After about an hour and a half, agents—or perhaps they were hotel security—opened the front door momentarily to yell at those outside. People crowded in front of the doors and yanked them open, as the agents and security inside scrambled to retreat. Both the outer and inner sliding doors of the lobby were forced open and people crowded into the vestibule. Chanting “Fuck ICE!”, the crowd forced the doors to unhook and swing open completely, facing off against an agent and some hotel security. By this point, most of the windows had been painted. A lone Minneapolis police officer forced his way through the crowd to join the agents.

For about an hour, he was the only law enforcement there, repeatedly pelted in the face with snow and screamed at by the crowd. There was a small row of people in the front at the vestibule, a larger row of streamers and press filming and taking photos, and then the rest of the crowd behind them. People threw snowballs and trash over the heads of the press. Some young women drummed on a trash can by the entrance; their friends danced together while other protestors grabbed the contents of the can to throw inside. The agent and security attempted to barricade the entrance with vending machines, which repeatedly fell back on them. The lobby filled with trash. Eventually, a window shattered, and people took videos of masked and helmeted ICE agents leaving out the back door with their luggage.

While this was happening, people went into the parking lot and checked all of the license plates against the massive database of known ICE plates that Minnesotans have been collecting for months. The plates of two known ICE cars were announced through a megaphone, and by the end of the night, the cars had been smashed and painted.

By this point, the building had been damaged, agents’ cars wrecked, and the agents were evacuating. Three hours after the noise demo began, three federal agents from the Bureau of Prisons showed up with firearms and deployed tear gas. After waving their guns around wildly and escorting the agents out of the hotel with their luggage, they eventually called for backup against what was by then a much smaller crowd of mostly press. One of the BOP federal agents was hit in the head by a flying object. Finally, additional federal officers arrived and deployed tear gas, flash-bang grenades, and green smoke, as well as large numbers of Minneapolis Police attempting to carry out a mass arrest. They arrested several members of the press and some protesters, but most people had already left.

Setting up a noise demonstration is relatively straightforward: someone had to confirm where ICE was staying, choose the most promising location, pick a time, make a flier, and spread it around. But it was only possible to do so quickly because of cumulative months of building networks and collecting information. The infrastructure of hotel and license plate databases equipped people to make a snap decision about which hotel to target. Likewise, the courage with which people built barricades, blocked the street with their cars, and confronted the agents in the hotel emerged from months of confrontation in the Twin Cities. It did not hurt that people were able to see the agents on the premises—they were there filming us and trying to figure out what to do.

The noise demonstrations represent an effective use of secondary targeting. In the Twin Cities, hotel noise demos have offered another way to address agents at a fixed location where they lack the defenses and organizational structures that they have at the Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building. Most of the confrontations in the Twin Cities have arisen out of spontaneous responses to raids, with a few taking place at the Whipple building; while the immediate responses to raids are critical and the demonstrations at the federal building have enabled activists to exert pressure on a choke point at the time of their choosing, the hotels are stationary targets with fewer defenses. Publicizing the noise demonstrations in advance can give the cops time to prepare a response, but people should prepare creatively and not let this deter them.

When there are no better options on the table, people will join symbolic marches or stay at home. But when options are available, many people will seize the opportunity to act courageously and effectively. In places that are not under overt federal occupation, where the lower density of ICE agents or ICE-watch organizing can make it more difficult to respond in time to ICE raids, finding secondary targets can offer a way forward, whether those are hotels, contractors, local officials, or business collaborators.

Further Reading

- Minneapolis Responds to the Murder of Alex Pretti: An Eyewitness Account

- Protesters Blockade ICE Headquarters in Fort Snelling, Minnesota: Report from an Action during the General Strike in the Twin Cities

- From Rapid Response to Revolutionary Social Change: The Potential of the Rapid Response Networks

- Rapid Response Networks in the Twin Cities: A Guide to an Updated Model

- North Minneapolis Chases Out ICE: A Firsthand Account of the Response to Another ICE Shooting

- Minneapolis Responds to ICE Committing Murder: An Account from the Streets

- Protesters Clash with ICE Agents Again in the Twin Cities: A Firsthand Report

- Minneapolis to Feds: “Get the Fuck Out”: How People in the Twin Cities Responded to a Federal Raid